A one-time move to legalise homes for landless residents tests Goa’s ability to protect centuries-old community land traditions

The Goa Legislative Diploma No. 2070 dated 15 April 1961 (Amendment) Bill, 2025, also known as Bill No. 39 of 2025, has ignited one of the most intense policy debates in recent years. At its core, the Bill proposes the insertion of a new Article 372-B into the Code, creating a one time, structured mechanism to regularise dwelling houses built before 28 February 2014 on land belonging to a Comunidade without lawful grant. The measure applies exclusively to landless individuals and overrides several other State laws, including the Goa Land Revenue Code, the Town and Country Planning Act and the laws governing municipal, panchayat and corporation jurisdictions. The Bill sets strict eligibility conditions. Applicants must have been residents of Goa for at least 15 years prior to the cut off date and must not own any other land, house, flat or ancestral property share. The regularisable area is limited to the plinth area of the dwelling house plus a two metre margin on all sides, where available, with a maximum ceiling of 300 square metres. Any additional encroached land must be surrendered to the Administrator for return to the Comunidade. Where houses stand in close proximity, the surrounding space will be proportionally divided.

Certain areas are completely excluded from the scope of regularisation. These include agricultural land under tenancy, protected forests, wildlife sanctuaries, constructions in the Coastal Regulation Zone after 19 February 1991, No Development Zones, open spaces, Eco-Sensitive Zone-I, khazan land, road setbacks, natural water channels and land reclaimed from water bodies. Areas in Eco-Sensitive Zone-II are also excluded except for orchard or cultivable land. The Bill permits regularisation only in zones classified as Settlement, Institutional, Industrial, Cultivable, or Orchard. A central provision is the requirement for the consent of the concerned Comunidade. This consent can be explicit, granted formally through its attorney, or deemed if the Comunidade fails to respond within the stipulated timeframe. Applicants must seek consent immediately upon filing their request. The Comunidade then has thirty days to decide, with refusals to be communicated within 15 days and supported by reasons. If no decision or communication is made within 45 days, consent will be deemed granted and the Administrator will issue a certificate within thirty days confirming it. Deemed consent may also be applied if the applicant has been in peaceful possession for at least twelve years without legal challenge or if the Comunidade or its committee members have previously issued informal permissions or accepted payments without following legal procedures. Refusals can be appealed to the Administrator within thirty days, and the Government may review the Administrator’s decision. Once consent is obtained, the authorised officer will notify the Comunidade’s attorney, allow fifteen days for a reply, conduct an enquiry and then issue an order. Land that is regularised under this process cannot be sold or transferred for 20 years except as a gift to a family member. Once the land title is secured, the owner may apply under the Goa Regularisation of Unauthorized Construction Act, 2016 for regularisation of the building itself.

The Bill also provides temporary protection from demolition. For 6 months after the law comes into force, eligible houses will be safeguarded and if an application is filed during that period, protection will continue until the case is decided. If no application is made or if it is rejected, the Administrator must initiate action as per the law. To deter misuse, the Bill imposes penalties for false claims, including cancellation of regularisation, reversion of the land to the Comunidade, fines of up to 100000 rupees and imprisonment for up to 2 years. Such offences are cognisable and can only be tried by a Judicial Magistrate First Class.

Chief Minister Dr Pramod Sawant has described the Bill as a carefully considered humanitarian measure. He stated that it is intended to provide dignity and security to long-standing occupants without undermining the rights of Comunidades. The maximum permissible area remains fixed at 300 square metres and both consent and compensation to the concerned Comunidade are mandatory. Protected zones such as forests, CRZ areas after 1991 and tenanted agricultural land will remain ineligible. The government estimates that 19,259 families will benefit from the measure, including 14,302 Goan families and 4,957 non-Goan families.

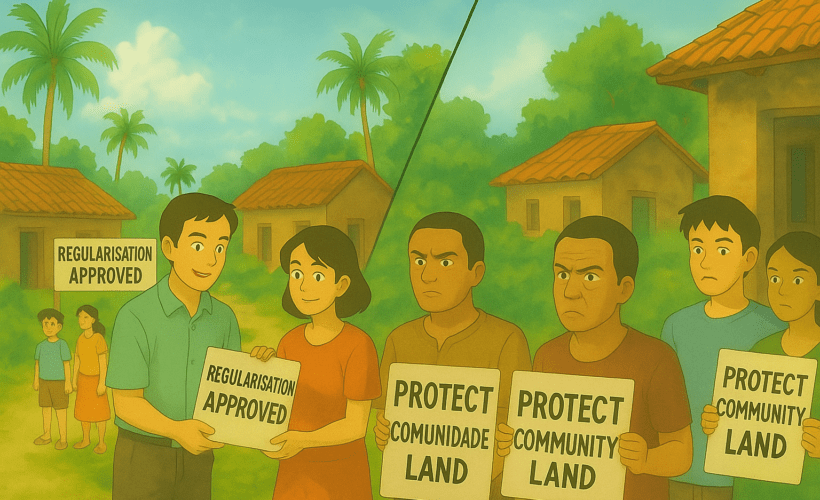

Under the Save Goa Save Comunidade movement, Comunidades across Bardez and other parts of the state have voiced strong opposition to the government’s decision to legalise houses built on Comunidade land, which they assert is private property protected under the Code of Comunidade. Leaders such as Nelson Fernandes and Ruildo D’Souza warned that the move legitimises illegal occupation, sets a dangerous precedent for institutional land grabbing, and threatens Goa’s cultural heritage and unique land ownership system. Joined by Comunidades from Nerul, Moira, Bastora, Nachinola and others, they stressed the thousand-year legacy of the institution and the need to safeguard it from politically driven policies that encourage further encroachments. The Save Goa campaign gained further momentum when 67 Comunidade Presidents convened in Chinchinim, unanimously resolving to challenge the decision in the Supreme Court, viewing it as a direct threat to heritage, ecology, and traditional land rights. However, with the Bill already passed in the Assembly, the government’s regularisation policy has moved forward ready for implementation.

At its heart, the debate over Bill No. 39 of 2025 represents a clash between the humanitarian goal of providing relief to long term occupants and the imperative to protect the heritage, autonomy, and legal integrity of the Comunidade system. The government views the Bill as a balanced measure that combines social justice with safeguards against abuse, while the Comunidades see it as a step that could permanently alter the character of their lands and governance structures. With court approval now secured, the legislation has moved beyond the stage of political argument and into active implementation, ensuring that one of Goa’s most sensitive land issues will be tested in practice reconciling the housing needs of residents with the preservation of a centuries-old community institution.